Brokeback Mountain saddles up

Brokeback Mountains reputation preceded it. I first began hearing about the gay cowboy movie about a year ago, on the premise that it was about two, well, gay cowboys. Naturally, I was intrigued.

Since Brokeback’s release on Dec. 19, it has won three Golden Globes, including Best Picture, Best Script (by Larry McMurtry and Diana Ossana), and Best Director (Ang Lee). Despite controversy that has trailed it across the country, the critically acclaimed film has been, in the large part, embraced.

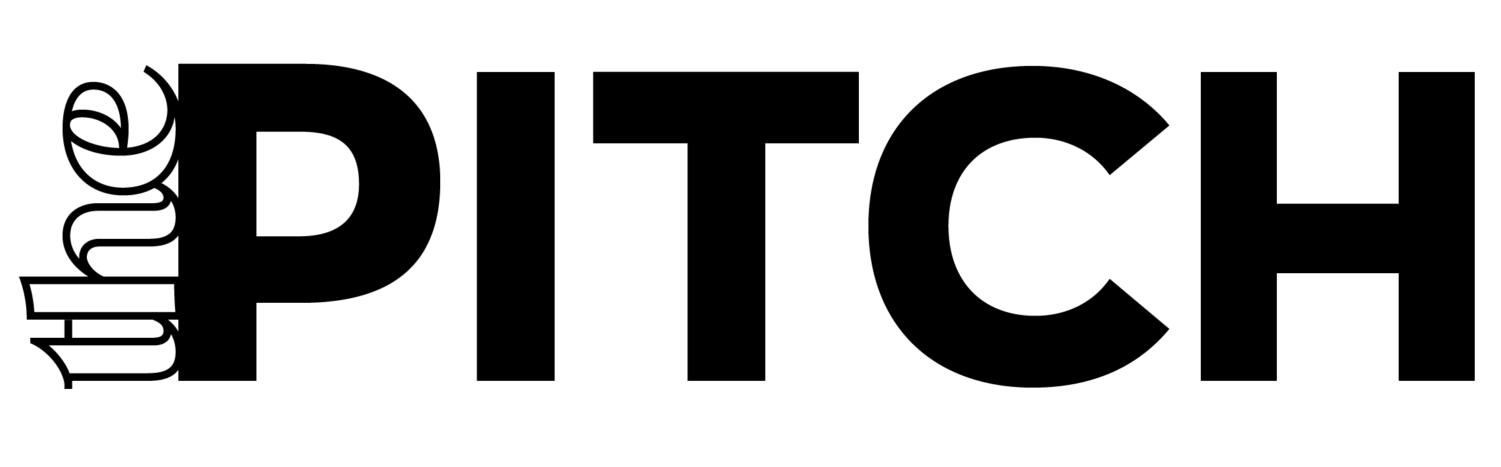

In any movie dealing with controversial issues, it is important for the director and writers to approach the subject matter delicately. At first, Brokeback seems to be dressed up like a child on Halloween, hoping to disguise itself as something else. Panoramic scenes with cinematography that even ComAcaders appreciate and two relatively large names, Heath Ledger and Jake Gyllenhaal, give Brokeback the feel of a “big picture.”

A few moments into the film, any preconceptions are dispelled. Director Lee has not crcated a film as political propaganda. He does not wave a rainbow flag or involve his characters in the gay rights movement. There are no secret agendas behind those daunting mountain ranges, behind Ledger’s wooden frown. It is what it is.

That is why Brokeback is so effective. Contrary to its two main characters, the tortured, reclusive Ennis Del Mar (Ledger) and the outgoing, charismatic Jack Twist (Gyllenhaal, who uses his enormous blue eyes to their full potential, ensnaring Ennis and the entire audience), the movie does not try to shy away from what it is.

This film is not about being gay. It is about being in love. It is about forbidden love, the same love presented in Romeo Juliet or Casablanca. It is about love that we cannot ignore, that we cannot place into a neat box, that we cannot stifle.

Perhaps it is no shock, then, that the movie is so powerful. In a world where Britney Spears can marry and get her marriage annulled in one night, we begin to wonder why two people so in love can’t be open about their relationship?

The men in Brokeback Mountain are not the faming homosexuals of common stereotype. They are not sexual predators, looking for other men to snare into their nets. When Del Mar and Twist share a tent on a cold night and end up acting on their desire for intimacy, the audience understands that this action is not an “abomination,” as the Bible would label it.

Brokeback shows us, most of all, that we cannot help with whom we fall in love. As Twist says to Del Mar, “I wish I knew how to quit you, we ache for him, knowing that it would be easier for him if he could do just that, and knowing that he can’t. Love, it seems, is relentless.

Despite its purposeful evasion of such political issues as gay marriage, the implicit lesson is well understood. Do we really want to live in a world where people cannot publicly love each other, regardless of their sexual orientation? Where people must fear for their lives because of the people they love?

In a world filled with war, famine, and death, do we want to stifle love?

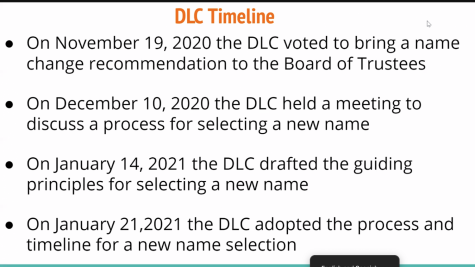

Your donation will support the student journalists of Archie Williams High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs. Each donation will receive a magazine subscription for a year (6 copies a year), and become a part of the important work our publication is doing.

$35 -- Subscription to the magazine

$50 -- Silver Sponsorship

$75 -- Gold Sponsorship

$100 -- Platinum Sponsorship