The unheard impact of distance learning on students with impaired hearing

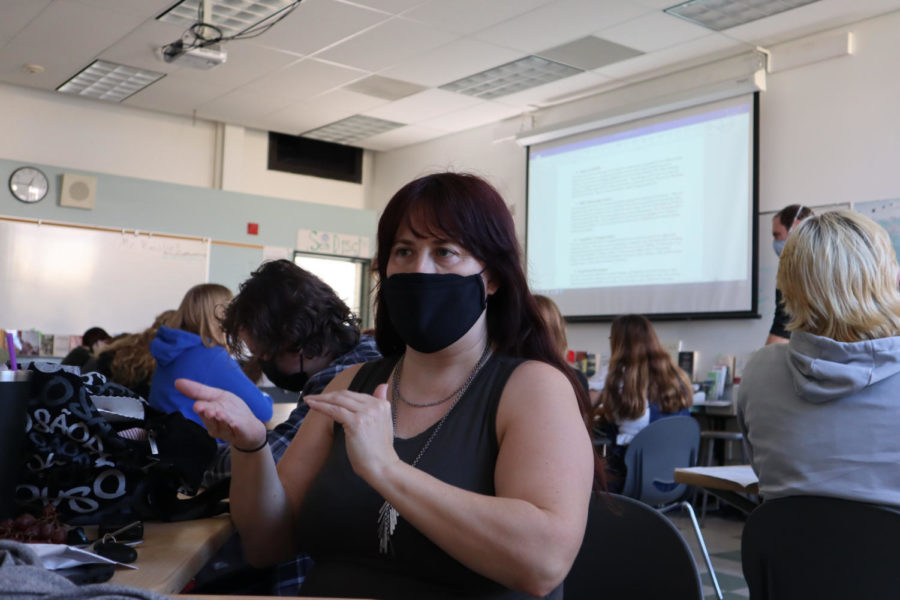

Interpreter Danelle Edwards communicates to junior Gia de Palma with sign language.

As a key aspect of learning, many students rely on communication with teachers and classmates to help them complete their assignments and work on group projects. However, for students across the world who have impaired hearing, communication is an obstacle to overcome.

According to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, around 0.03 percent of children in the United States are born with a detectable level of hearing loss in one or both ears. Children with hearing loss/impaired hearing must discover ways to succeed in a school environment without full access to all human senses.

In order to provide hearing-impaired students with additional support to succeed in traditional learning environments, they are often given an educational interpreter. In 2019, the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that in 2019, there were 77,400 interpreters in schools, hospitals, courtrooms, and meeting rooms throughout the country.

Danelle Edwards, a sign language interpreter contracted with the Tamalpais Union High School District (TUHSD), started working as an interpreter 17 years ago. Edwards learned sign language when she worked as a teacher’s aid in the Deaf and Hard of Hearing Program at the Sonoma School District in Santa Rosa for five years. Per the annually renewed contract Edwards has with TUHSD, her job is to help one student with communication access in learning and ensure that the student can fully understand all information given to them by sound.

Archie Williams High School (AWHS) junior Gia De Palma started working with Edwards when she was in first grade. Over the years, they have developed an understanding of one another and bonded in order to make school a safe space for Gia. Edwards provides support to Gia whenever she needs it, to help with school work, teachers, and resources.

“I have had her for, I don’t even know how many years, but from first grade to eleventh grade,” Gia said. “So we get along really well, and it’s just easy with her. Usually [school] is more difficult at the beginning of the year because you have to get to know people, so you have to get to know how they talk, but usually it’s easy.”

Gia’s parents found out she had impaired hearing when she was 18 months old, when Gia was on a walk with two family friends and their daughter who was Gia’s age.

“An ambulance drove by and I didn’t cry at all and the other girl burst into tears. The other mom realized that something was up,” Gia said.

Sign was Gia’s first language, which her parents and preschool teachers taught to her. Though Gia can understand American Sign Language (ASL), she does not normally use it. She was taught sign language exact English instead of ASL.

“I technically learned signing exact English, which is basically a different language because ASL is entirely different, with different word orders and structures and is much more complicated,” Gia said. “I do know sign, which can translate over to ASL, but it’s complicated.”

Every school year, Edwards and the school board have an Individualized Education Program (IEP) meeting to discuss Gia’s schooling and class placement for that year.

“We discuss the best way to work with an interpreter and, you know, class placement to have Gia and I in a space where we can access both the teacher, the board and I,” Edwards said.

Gia and Edwards worked together in-person for years, however, midway through Gia’s freshman year, COVID-19 presented a new challenge. Gia was forced to start doing school on Zoom, causing Edwards to brainstorm ways she could help Gia virtually. Edwards and Gia decided it was necessary to have three devices each in order to keep up with schooling, communicate with teachers, and to fully understand the classes.

“We would each have a computer with the Zoom class, we would each have an iPad to FaceTime each other, and we would also have a phone to text each other just in case one of the devices was not working,” Edwards said.

Edwards, however, also found herself with days where she would have nothing to do because Gia would just be given independent schoolwork. Gia would then work on her assignments on her own, and Edwards would assist when needed.

Facing similar obstacles to Gia in the past couple years, AWHS junior Kaitlyn Signor has profound hearing, meaning she can only hear sounds that are over 95dB. This means Kaitlyn can only hear sounds of a higher volume. She has cochlear implants, which are surgically implanted neuroprosthesis that provide her with sound perception.

Kaitlyn had an interpreter until she went into sixth grade, when she decided that she could succeed in school and classes on her own. Instead of an interpreter, Kaitlyn now has a Roger Pen (a wireless microphone transmitter) that helps her communicate with classmates, friends, and family.

Cochlear implants can also give people with profound hearing the opportunity to improve their speech. With the Roger Pen, Kaitlyn can hear her classmates better and build understanding in both quiet and noisy environments.

Kaitlyn said that her experience on Zoom was relatively easy because she could see her classmates’ mouths and because of Zoom’s closed captioning feature. However, during online school Kaitlyn missed in-person connections and communication.

“I felt like I was not connected socially and not getting enough fresh air, which are good things to have for my mental and physical health,” Kaitlyn said.

When coming back to school after Zoom, Gia and Kaitlyn both say that the hardest thing to deal with is masks, as they can’t see people’s mouths when communicating in-person. They ask people to speak up and pull their masks down when talking to them, and Kaitlyn usually holds her Roger Pen up to people in order to hear them.

“It is definitely more difficult with masks. I have to rely much more on my sign interpreter because I can’t lip read, which really sucks. I have gotten used to it, but I am really looking forward to when we go back to wearing no masks,” Gia said.

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, almpandemicost everyone had to find new ways to connect. But for those with impaired hearing, this was even more challenging. During this struggle, Gia, Kaitlyn, and other hearing impaired students persevered to find new ways to communicate with their interpreters and excel in school, and are now more resilient than ever before.

Neve is a sophomore, in her second year of journalism. She loves water and nature, reading, and hanging out with friends. You can find Neve in her room...

Ezra is a sophomore who has been in journalism for a year and a half. In his free time he likes playing basketball, and you can often find him working...

Elliot is a senior, in his third year of journalism. He loves eating chicken pot pie and playing soccer. You can often find him watching Spongebob. He...