Younger generations meld new religious communities in school

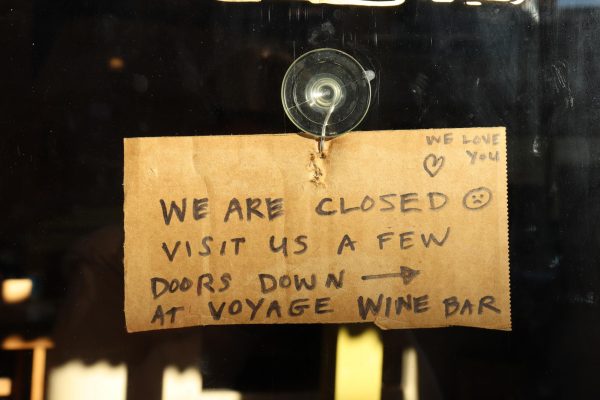

Across from the Fairfax library, the crosses atop the Saint Rita Church shine.

Separation of church and state is one of America’s defining factors as a country. No religion in the government, no religion in sports, and no religion in public schools. Despite these regulations, which are constantly tossed around in the Supreme Court, students of diverse, individual beliefs and spirituality have found community at Archie Williams.

Aligning with the political demographics of a left leaning county, a majority of Marin’s religious affiliation is no affiliation at all. According to a study done by Pew Research center, 69 percent of atheists in the United States identify as Democratic. As one of the most liberal counties in California (82.3 percent of Marin residents voted blue in the 2020 election), Marin lines up with the general demographics of America’s atheist and agnostic population.

Among Archie Williams’ student demographics, atheist and agnostic beliefs remain the most prevalent. However, Catholicism, Islam, Hinduism, Judaism, and other religions maintain representation in different proportions throughout the school. Catholic and Jewish students in particular have found a way to create a sense of community among their religious peers.

Among Archie Williams’ student-run organizations, Jewish Culture Club hosts weekly meetings for Archie Williams’ Jewish population to share, discuss and celebrate the culture of their religion with each other and non-Jewish students. Sophomore Paige Murphy, who is Jewish, looks forward to the weekly club meetings.

“I think the fact that the club is [focused on] learning about the culture of Judaism and not necessarily the religion,” Paige said. “It makes me feel more safe [at school] because people are open to learning about the culture of Judaism and not just the religion.”

Unlike starting most student-run clubs, the validity of hosting a religious club at school is continuously debated among the levels of state and federal courts. The most famous, West Side Community Schools v. Mergens (1990) ruled in favor of religious and political clubs, arguing that any discrimination against religious or political clubs defies the Equal Access Act of 1984. By definition, this act will cut off funding for a public school if it fails to uphold students’ access to the First Amendment, the right to free religion.

On the other side of the First Amendment lies the separation of church and state, prohibiting a government-funded entity to promote one religion over the other. Translated to public schools, this means equal representation of all religions in classes. Taber Watson, a Government and History teacher at Archie Williams, makes an effort to expose students to all religions through his curriculum.

“I would say it is impossible to teach history, particularly world history, without mentioning religion, it would actually be irresponsible to do so… [our curriculum] is very much a third party bird’s eye view of religion,” Watson said. “Unless [religious teachings] are actively pushing the history curriculum forward, I don’t think you’ll find a teacher who’s diving into it much more than that.”

Discussing all religions equally and honestly in schools creates a level playing field for students of different religious beliefs to learn. At the same time, necessary education creates prejudices and stereotypes towards specific religions. Sophomore Maya Estrada believes that what her peers learn, from not only school but media, friends, and community, can produce harmful ideas of how members of certain religions act.

“I sometimes don’t feel 100 percent accepted because when I do wear [a cross necklace] and I get questions about it I’ll speak on it and speak on my opinions of just Catholicism,” Maya said. “A lot of the time people will just say that I’m either racist or homophobic automatically and that’s definitely not the case, but just a stereotype.”.

Similar to Maya, junior Mikayla Silverstein felt uncomfortable as a Jewish child surrounded by her Christian or unaffiliated peers.

“In elementary school, you’d have Christmas parties and holiday parties, and [religious promotion is] more prevalent there,” Mikayla said.

Aside from representation in school, today’s youth define religion differently than those of generations past. Compared to the traditional idea of weekly worship, religious community service, and studying of religious texts, modern ideas of religious practice are more laid back. Youth groups have become widely popular among Christian teenagers. A safe community space to gather and spend time with people of a similar religion in a nontraditional way, youth groups provide teenagers with a modern and approachable religious practice.

Unlike past generations’ idea of faith, many Marin youth have created a more loosely defined, yet still connected, relationship with religion. Archie Williams senior Aidan Gilmartin defined his idea of religion.

“I think that religion has a role in my life. I wouldn’t say it’s a die hard part of my life. I’d like to think that I pray a lot, and that I give thanks if that means anything,” Aidan said. “I find that having something to pray to, or look up to, or to say there’s a reason for being here and something after death is a secure thought.”

Jasmin is a senior, in her third year of journalism. She enjoys eating grapes and pretzels at the same time. You can often find her listening to Bad Bunny...

Ezra is a sophomore who has been in journalism for a year and a half. In his free time he likes playing basketball, and you can often find him working...