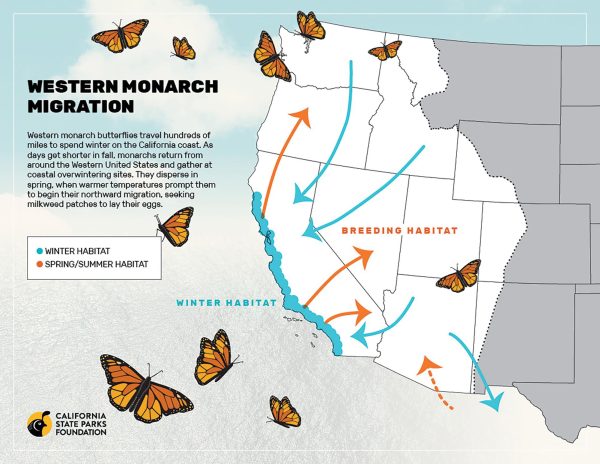

From August through November, western monarch butterflies complete their migration from west of the Rocky Mountains to Southern California and Mexico, passing through the Bay Area. On their extensive 3,000 mile journey, western monarchs travel through the Bay Area to roost in several small overwintering sites, areas where they stay warm in the cold season. The monarch is the only butterfly to make a two-way migration, traveling to and from these locations annually, referred to by many as a “natural phenomenon.”

One direction of monarchs’ migrations takes them to the mountains, to experience a milder summer. This migration is segmented by four or five generations, as each group only has about six weeks to live and fly, before they die and their offspring continue the journey.

The migration of first-generation butterflies begins in spring just off the coast of Southern California and Mexico. After migrating inland, the butterflies seek a mate to fertilize and lay eggs, which grow to become the second generation to continue the northward migration. Successive generations follow the same pattern, each group moving incrementally farther inland, a phenomenon called generational migration.

“[Generational migration is] how they rebuild the population, because each generation makes the population bigger and bigger and expands throughout the West,” said Mia Monroe, a former park ranger and current volunteer with the Xerces Society, a nonprofit dedicated to invertebrate conservation.

The fourth or fifth generation is born in the mountains, and that single generation of butterflies, the last of their migration cycle, flies the entirety of the final leg back to the coast for winter. Most monarchs only live for four to six weeks, but the final generation that flies back south can live for eight or nine to be able to make the journey.

Monarchs migrate due to survival instincts based upon seasonal weather patterns, food, and reproductive needs. Where and when monarchs migrate is approximate and based on previous years’ trends that scientists count annually in November.

Audrey Fusco is a restoration ecologist and native plant nursery manager with Turtle Island Restoration Network (TIRN) and works to support wildlife by supporting their habitats. Her work has been significant to pollinators such as the western monarch, following their success and migratory habits as a population.

“They don’t have just one straight pathway that every generation successively follows. They just go where they wanna go, and they mostly seem to be migrating in search of resources like nectar and milkweed,” Fusco said.

In the fall months, the final generation of this migratory pattern of monarchs travels from their mountainous summer homes to the warm coast of California and Mexico. Here, they overwinter, the process of keeping themselves warm in the coldest months. The Bay Area harbors multiple overwintering locations, including Bolinas, Stinson Beach, and Muir Beach. Along their migratory routes, monarchs must find roosts in pine, fir, and cedar trees at night because of temperature sensitivity.

After making their journey, monarchs enter a diapause where their reproductive hormones shut down for the winter in order to focus on survival before reproduction in early spring. The offspring of these butterflies are the first generation of the following migratory cycle.

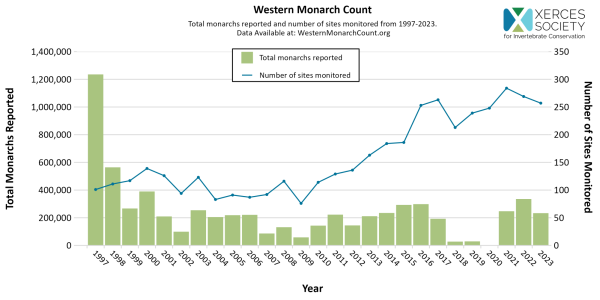

According to the Xerces Society, over recent generations, the western monarch population has diminished. In 1997, the population count was around 1.2 million. A decade later, it dropped to roughly 90,000, and in 2020, it dramatically decreased to 1,914. By 2020, the monarch population made up only 0.16 percent of its size in 1997.

“I’ve been watching monarch populations for decades, for about 40 years. I remember when there were millions of monarchs that made their way to the coast in the winter. In 2020 there were less than 2,000. In the places I visited [previously], I couldn’t find monarchs at all,” Monroe said.

For most endangered species, scientists set an extinction vortex number, meaning that when the population hits that number, it will be unable or unlikely to recover. The monarch butterflies’ extinction vortex number was set at 30,000 in 2017, which they reached the following year. This rapid population decline results from habitat loss, including a lack of milkweed, the plant that monarchs lay their eggs on, and decreased nectar sources.

Additionally, California wildfires have burned through monarch habitats, including milkweed and tree roosts. The wildfires increased throughout 2020, and habitat destruction along the migration route severely impacted the already diminishing population.

Monarchs, as pollinators, make vital contributions to nature and play a crucial role in the reproduction of plants, allowing a variety of wildlife to thrive. Pollination by monarchs aids in food security efforts by supporting a variety of crops.

“People often think about pollination and its value to things like our orchards and our food crops, but all the pollinators, like monarchs, are also pollinating California native plants at the same time. So they’re moving pollen around from nectar plant to nectar plant, and they’re hoping to encourage more of those plants to grow. They’re performing basic ecosystem services,” Fusco said.

According to Fusco, in addition to their ecological significance, monarchs also hold symbolic importance.

“The monarch has this beautiful story [of being] an iconic species, [one] of significance in many ways, including potentially spiritual significance to cultures. It’s a species that represents the renewal of life… so we really want to keep it around,” Fusco said.

With the help of many devoted gardeners, citizens, and experts, the monarch population has seen a significant increase since 2020. As of November 2023, there were a little over 200,000 monarchs. Despite this vast improvement, the work is not over.

Monarchs continue to need conservation efforts and habitat restoration. Limiting or eradicating pesticides, herbicides, and nitrogen-heavy fertilizers assists monarch habitats, as well asplanting milkweed and other native nectar plants.

Archie Williams has participated in monarch habitat restoration through work in the school garden. By planting milkweed and pollinator plants, the Archie Williams Social and Environmental Academy-Dedicated to Improving School Community (SEA-DISC) and the Garden Club work to support monarchs in their gardening efforts.

“The garden club left a really nice patch of milkweed in the back that should be enough to support a good population of monarchs. [SEA-DISC] will keep planting more [milkweed] in there too,” said Archie Williams SEA-DISC teacher Michael Rawlins.

It is important to ensure that milkweed is native to the area it is planted in. In warm California climates, non-native tropical milkweed can develop pathogens on the plant that transmit parasites to the monarchs.

The location of milkweed also impacts monarch survival. Planting too close to the coast tempts butterflies to stay in their overwintering sites and lay eggs on the milkweed after exiting their reproductive diapause. That causes the first-generation butterflies to be born on the coast, disrupting the migratory patterns. Planting native milkweed in non-coastal areas makes a remarkable difference in monarch prosperity.

Monroe encourages viewers of monarchs to contribute to online recording databases, such as the online program iNaturalist.

“We can each be a community scientist by observing and sharing what we see and therefore contributing to the bigger database. If you see a monarch butterfly, [you can log it on] iNaturalist, a free app that encourages you to be an active observer of the natural world,” Monroe said.

California is home to many monarch hotspots, such as Pacific Grove, Pismo State Beach, and more locally, the Marin Headlands and Bolinas, as well as the butterfly dome at the California Academy of Sciences. Monroe hopes Marin citizens remember to appreciate the beauty and biodiversity as the monarchs make their way through Northern California in the fall months. For Monroe, September, Biodiversity Month, signals a time to recognize and protect the natural world.

“[In September,] we’re celebrating how amazing our country is at supporting so many different life forms,” Monroe said.